PROYECTOS | PROJECTS

Weaving Two Languages

Three major outcomes of language contact are convergence, borrowing and code-switching. In grammatical convergence, languages become structurally more similar. In borrowing, single words from one language, usually nouns, are incorporated into the other through grammatical integration. In code-switching, bilinguals go back and forth between the two languages, in alternating multiword strings.

Gauging Convergence on the Ground

PIs: Rena Torres Cacoullos and Catherine E. Travis

But does using two languages lead to grammatical change? Does code-switching result in Spanish becoming grammatically similar to English? Analyzing hundreds of thousands of words in a corpus of NM bilinguals’ everyday speech reveals patterns of variation. An example is variable subject pronoun expression: subject pronouns are less likely when the preceding subject was the same, as in the second line of the first example.

In English, variable subject expression is restricted to initial prosodic position. For example, the subject I is unexpressed in the fourth and fifth lines of the second example.

Example 1:

yo no lo conocí.

.. pero Ø me imagino que sí.

[NMSEB 04, 09:29-09:32]

Example 2:

.. I was able to scramble and,

.. find the —

my other flashlight,

… Ø turned it on,

Ø worked on the one that I had just broke.

[NMSEB 16, 26:06-26:12]

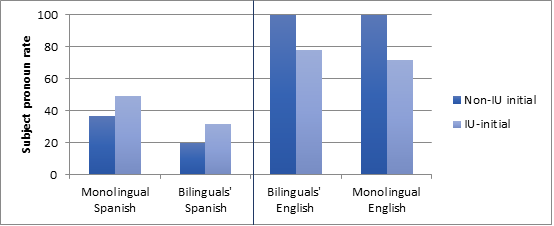

Quantitative diagnostics of grammatical similarity, based on patterns of variation, show that bilinguals’ Spanish and English align with their respective monolingual benchmarks. Notice that bilinguals maintain the different subject-pronoun patterns of the two languages.

Subject pronoun rate according to the prosodic position of the verb, comparing Spanish and English. (IU=Intonation Unit)

National Science Foundation: BCS 1019112/1019122 [2010-2013]

Combining Languages through Code-switching

PIs: Rena Torres Cacoullos and Shana Poplack

Code-switches internally follow the grammar of their respective language but occur at boundaries where the two languages have the same word order. This is the Equivalence Constraint (Poplack 1980). But how do bilinguals deal with language boundaries where there is variable equivalence?

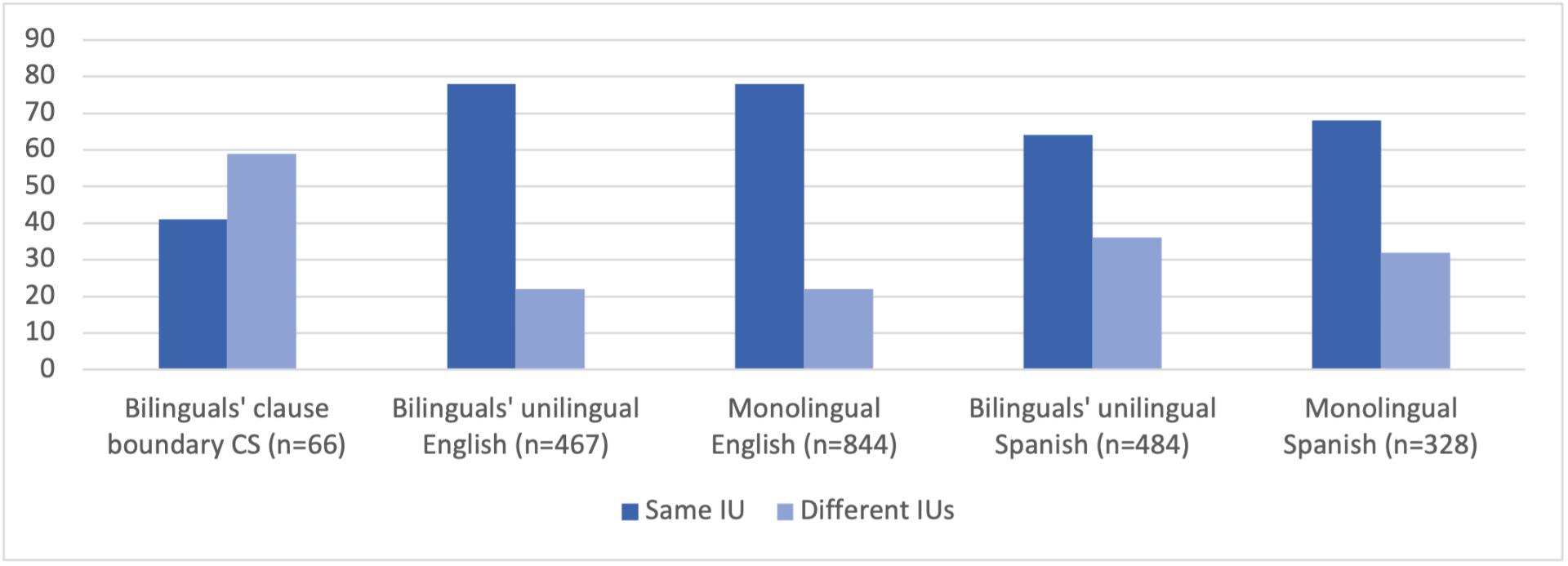

For example, the boundary between main and complement clauses is variably equivalent: ‘que’ is used always in Spanish but ‘that’ is used only sometimes. Here a bilingual prosodic strategy is to separate the boundary between the languages. Main and complement clauses in the same language tend to be in the same Intonation Unit, but when they are in different languages they tend to be in different Intonation Units.

A syntactic bilingual strategy is to prefer Spanish ‘que’ over English ‘that’ at the boundary, regardless of the direction of switching. Bilinguals choose Spanish ‘que’ because it is the more frequent and automatic option.

so I told them,

que van a salir en el Sun.

[NMSEB 22, 17:05-17:08]

me dijeron que,

I was gonna run the !two mile?

[NMSEB 22, 11:07-11:10]

National Science Foundation: BCS-1624966 [2016-2022]

Combining Languages through Borrowing

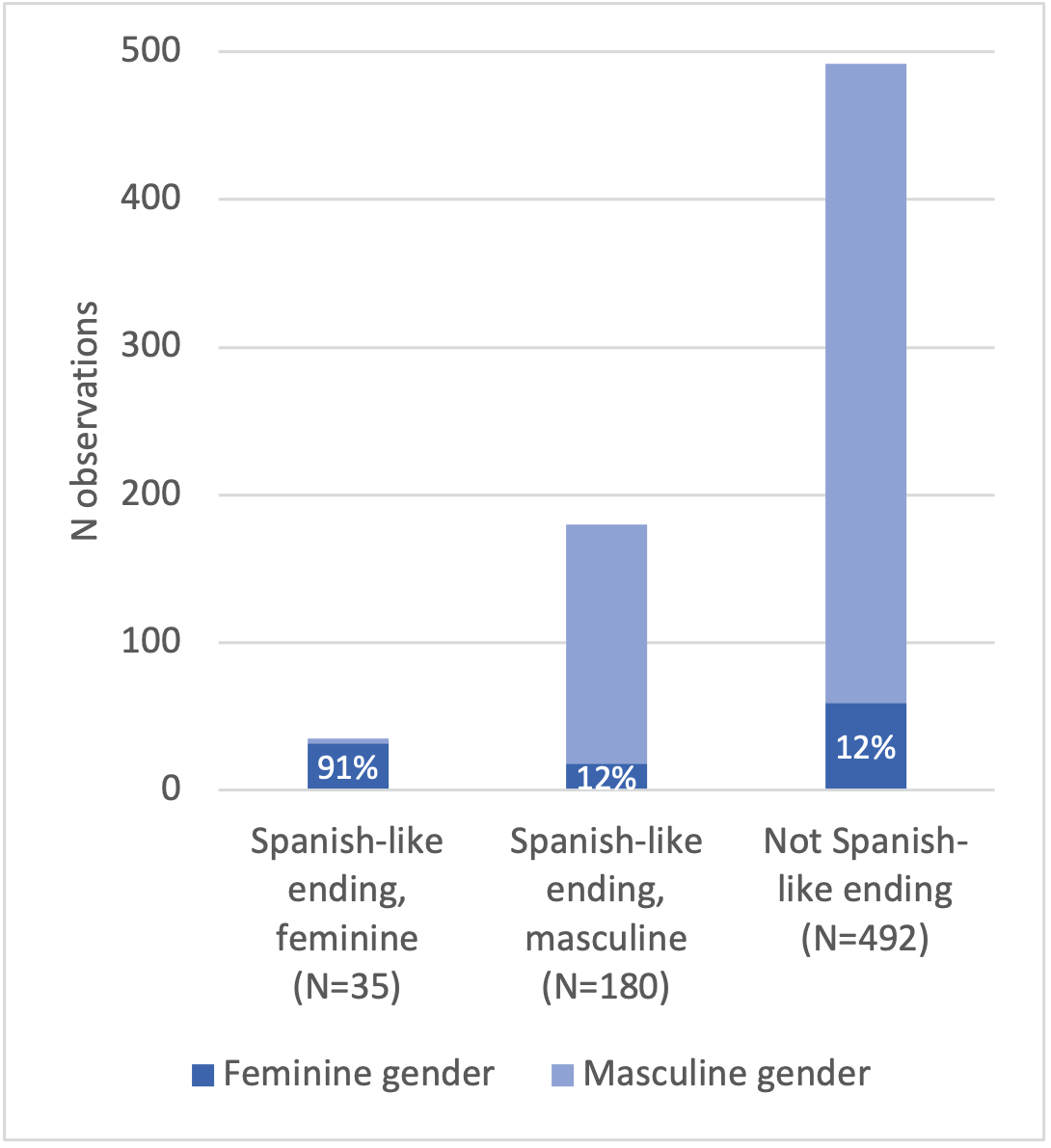

Consider English nouns integrated into Spanish, with which bilinguals use Spanish grammatical gender. This is mostly masculine, as in the first example, rather than feminine, as in the second one.

a nosotros se nos heló el drain.

[NMSEB 09, 34:04-34:06]

yo agarro la key.

[NMSEB 06, 38:44-38:46]

However, for Spanish nouns there is an even split between masculine and feminine. Why the discrepancy? In choosing the gender for English nouns, bilinguals sometimes consider the equivalent Spanish noun, as in the second example (compare la llave). But the strongest rule, just as for monolinguals, is the phonological ending of the word.

Rate of feminine grammatical gender for lone English nouns in Spanish according to their ending: English nouns in Spanish discourse tend to be used by bilinguals with Spanish feminine gender when their phonological ending is feminine Spanish-like, but most English nouns do not have a recognizably Spanish-like ending.

The reason for disproportionate masculine gender with English nouns is not a simplified masculine-for-all rule but the fact that most English nouns have unfamiliar endings for Spanish. So, masculine is used because it is more productive than feminine in Spanish, occurring with a greater range of endings. It is therefore the open pattern to be used with all novel nouns, including ones borrowed from English.

References

Keeping the Two Grammars Intact

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Travis, C. E. 2015. Gauging convergence on the ground: Code-switching in the community-Introduction. International Journal of Bilingualism 19.4: 365-386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516046

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Travis, C. E. 2019. Gramáticas en contacto en un corpus bilingüe. Corpus y construcciones. Perspectivas hispánicas, Blanco, M., H. Olbertz & V. Vázquez Rozas (eds.): Anexo 79 de Verba: 13-40. https://www.usc.gal/libros/es/92-verba_anuario_galego_de_filoloxa_anexos_issn_2341_1198

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Travis, C. E. 2018/2020. Bilingualism in the community: Code-switching and grammars in contact. Cambridge University Press.

Word Order

Benevento, N. M. & Dietrich, A. J. 2015. I think, therefore digo yo: Variable position of the 1sg subject pronoun in New Mexican Spanish-English code-switching. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(4): 407-422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516038

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Vélez Avilés. J. 2023. Mixing Adjectives: A variable equivalence hypothesis for word order conflicts. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.22038.tor

Tense-Aspect-Mood

Dumont, J. & Wilson, D. Vergara. 2016. Using the variationist comparative method to examine the role of language contact in synthetic and periphrastic verbs in Spanish. Spanish in Context 13 (3): 394 – 419. https://doi.org/10.1075/sic.13.3.04dum

LaCasse, D. & Torres Cacoullos, R. 2023. Simplification in bilinguals’ parallel structures? Spanish and English main-and-complement clauses. Mutual Influence in Situations of Spanish Language Contact in the Americas, M. Waltermire & K. Bove (eds). Routledge.

Differential Object Marking

Sankoff, D., Dion, N., Brandts, A., Alvo, M. Balasch, S. & Adams, J. 2015. Comparing variables in different corpora with context-based model-free variant probabilities. Linguistic variation: Confronting fact and theory, R. Torres Cacoullos, N. Dion & A. Lapierre (eds.), 335-345. Routledge.

Borrowing

Aaron, J. E. 2015. Lone English-origin nouns in Spanish: The precedence of community norms. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(4): 423-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516021

Torres Cacoullos, R. & LaCasse, D. 2024. Lone-words are grammatically loanwords. Chicago Linguistic Society 60 .pdf

Trawick, S. & Bero, T. 2022. Gender assignment: Monolingual constraints contribute to a bilingual outcome. International Journal of Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069211053466

Wilson, D. V. & Dumont, J. 2015. The emergent grammar of bilinguals: The Spanish verb hacer ‘do’ with a bare English infinitive. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(4): 444-458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516047

Code-switching

Balukas, C. & Koops, C. 2015. Spanish-English bilingual voice onset time in spontaneous code-switching. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(4): 459-480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516035

Brown, E. L. 2015. The role of discourse context frequency in phonological variation: A usage-based approach to bilingual speech production. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(4): 387-406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516042

Johns, M. & Steuck, J. 2021. Is codeswitching easy or difficult? Testing processing cost through the prosodic structure of bilingual speech. Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104634

Pattichis, R., LaCasse, D., Trawick, S. & Torres Cacoullos, R. 2023. Code-switching metrics using Intonation Units. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP).

Steuck, J. & Torres Cacoullos, R. 2019. Complementing in another language: Prosody and code-switching. Language variation – European Perspectives VII: Selected papers from the Ninth International Conference on Language Variation in Europe (ICLaVE 9), Malaga, June 2017, J. A. Villena Ponsoda et. al. (eds.), 219-231. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/silv.22.14ste

Torres Cacoullos, R. 2020. Code-switching strategies: prosody and syntax. Frontiers in Psychology https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02130

Torres Cacoullos, R. & LaCasse, D. 2024. Bilingual clause combining: A Variable Equivalence hypothesis for conjunction choice. International Journal of Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069241265587

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Travis, C. E. 2021. Code-switching and bilinguals’ grammars. The Routledge Handbook of Language Contact, Adamou & Matras (eds.), 252-275, Routledge.

Torres Cacoullos, R., Dion, N., LaCasse, D., Poplack, S. 2021. How to mix. Confronting “mixed” NP models and bilinguals’ choices. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.20017.tor

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Vélez Avilés. J. 2023. Mixing Adjectives: A variable equivalence hypothesis for word order conflicts. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.22038.tor

Cross-language Priming, with No Grammatical Change

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Travis, C .E. 2011. Testing convergence via code-switching: Priming and the structure of variable subject expression. International Journal of Bilingualism 15(3): 241-267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006910371025

Torres Cacoullos, R. & Travis, C. E. 2016. Two languages, one effect: Structural priming in spontaneous code-switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19(4): 733-753. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728914000406

Travis, C. E., Torres Cacoullos, R. & Kidd, E. 2017. Cross-language priming: A view from bilingual speech. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20(2): 283-298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728915000127